A force for change: Voices from the frontline

Five stories of change, five personal reflections

C&A Foundation began with an idea: that fashion could be a force for good.

We have always known that a different fashion industry is possible; one that is just, equitable and sustainable; one that works better for the very people who power the industry. We know it’s possible because we’ve seen it for ourselves. Our partners’ efforts have made meaningful, lasting change in their communities and in the wider fashion industry. We look forward to seeing what they achieve next.

Read five powerful stories of change and five personal reflections from C&A Foundation team members – selected for each of the five years C&A Foundation was working to make fashion a force for good.

Five years, five stories of change to remember

Earthquake: community reconstruction and strengthening

2 April 2019

Community Reconstruction and Strengthening: two actions implemented by Save the Children and the C&A Foundation just over a year after September 19, 2017

Adriana lives with her three children in a community near Tetela del Volcán, to the west of Morelos. On the afternoon of September 19, 2017, her home became one of the buildings that collapsed or received structural damage making them uninhabitable: “That day, the little house where I lived with my three children came tumbling down. After the earthquake, my brother lent me his kitchen to live in with my children, and he had to build an additional room with plywood. For a long time, I was sad, thinking about where I would live with my children in dignity,” she remembers.

She was not the only one to lose her home in that area, as nearby towns such as Tlalmimilulpan, Jumiltepec and Ocuituco were also hit by the earthquake. In Ocuituco, Gustavo and his family also had to leave their home: “Thank God we weren't at home. When we returned, we found it broken up. We had no other choice but to leave for the safety of my wife and my child. We built a room out of pallets in my mother’s house, and we tried to insulate it with nylon, cardboard and some plywood that we had so that the cold couldn’t get in. It is a very ugly thing to see how everything you had is destroyed in a second,” he said.

Fortunately, families like those of Gustavo and Adriana received assistance from Save The Children and its ally, the C&A Foundation, which donated half a million euros for immediate actions, and an additional half a million for reconstruction work in States such as Morelos, Oaxaca and Puebla. These actions focused on creating new homes for 15 families, who will soon receive their new quake-proof houses.

Israel is a leader in community mobilization for Save The Children in Morelos and has been overseeing the reconstruction process. Israel has noted that this process focuses not only on the creation of new homes, but also on supporting families who have lost everything: “Not only are we building houses, but we are also providing support to empower families. That is why we have come up with some ways to help support or resolve the situations faced with guidance from Save The Children,” he said. He and other volunteers spent time with approximately 60 families of victims, awarding reconstruction to 15 of them after applying several filters created to give those in greatest need a chance to start again.

Some of the actions by Save The Children to empower families include DIY construction workshops and the creation of comandas: organizational structures in which the families provide meals for the workers and are reimbursed by the organization. That led to the creation of a system that benefits everyone and integrates the workers into their community.

The workshops given by the social organization reviewed concepts that help prevent other accidents and provide the tools to overcome them. Those attending the workshops agreed to share the information so that more people learn about these concepts. In addition, the facilitators have helped reinforce the psychological and social support for boys, girls and teenagers, helping them overcome the situation they have lived through.

It won't be long now until Adriana, Gustavo and other families who were victims of the 2017 earthquake can rebuild their lives in their new houses, and they are very excited to have a place of their own again, to live in dignity: “There’s still almost a month until we will have a house again. It took nearly a year to have it again, but I thank God that we have another chance,” said Adriana.

Thanks to the actions of Save The Children, with the support of the C&A Foundation, 94,325 people (including 38,159 boys, girls and teenagers from Oaxaca, Puebla and Morelos) benefited immediately, and now another 15 families will once again have a home to live in.

“Since 2015, the C&A Foundation has allied with Save the Children to support them in saving lives, providing safe spaces for children and developing resilience in urban communities, especially in the garment-producing countries where we operate. We are proud to have provided backing in response to over 35 emergencies, and we hope to continue these successes through our collaboration in the coming years," said Executive Director of C&A Foundation, Leslie Johnston.

Connecting for collective action

10 July 2019

One complaint on a community media platform changed the future for 420 workers at this unit

Never looking back

A normal day at Padmavathi’s home is filled with the sounds of children getting ready for the day. As the children get ready, Padmavathi and her sister do the same, Padmavathi for the factory and her sister for the house. Afterwards, she checks school uniforms and bags before leaving for the factory.

At 40, Padmavathi is the sole bread winner of a family of seven. An accident, three years ago, left her husband bedridden and recently, her widowed sister arrived with her two children seeking support. Padmavathi is soldiering on with these personal responsibilities in addition to being a strong voice from her union advocating for fair wages.

She works as a stitcher in a garment factory in Manamadi Industrial area outside Chennai, Tamil Nadu in the southern region of India. Padmavathi joined the Garment and Fashion Workers Union (GAFWU) seven years ago to fight for her rights and hasn’t looked back since. Whether to secure social security through the Welfare Board or fight illegal deductions to her wage, the union’s support helped her and fellow workers in claiming their rights. Urimai Kural is an interactive voice response system (IVRS) powered by Gram Vaani’s community media platform. In 2017, Padmavathi submitted a complaint on this platform that was the catalyst required for change.

IVRS to reach workers far and wide

C&A Foundation and Gram Vaani partnered to develop Shramik Vaani (workers voice), an initiative that uses technology to strengthen awareness and foster collective action among workers. Gram Vaani has been building media platforms to empower communities to demand accountability since 2012. They use IVRS on mobile phones- easy to use and widely accessible in multiple locations in India. Urimai Kural is one of the four active IVRS platforms on this initiative. The platform is managed by unions, which in this case is GAFWU. Union leaders are trained by Gram Vaani on how to operate and manage the IVRS to enable stronger leadership by the union in using the platform. It helps streamline operations and connect workers in different parts of the country.

In 2017, Padmavathi lodged a complaint on Urimai Kural regarding her wages that brought about positive change for everyone. The state government raised the minimum wage in 2014, and the employers objected to this in court, leading to a two-year-long legal battle. The victory was bittersweet. Courts ordered companies to pay the new wage including arrears with immediate effect and they, in turn, decided to levy a fresh deduction for company provided transport. The workers were back to square one. Wages increased from Rs.6,000 (Eur 76) to Rs.8,000 (Eur 101) per month, and the hike was now being deducted for transport.

“I am getting Rs.5,000 in hand even without taking any leave. It has become difficult to support my family”, Padmavathi recalls the words of her complaint on Urimai Kural. The complaint was filed on September 10th, 2017, on behalf of 420 workers that commuted via company transport from her unit at the factory. This, in addition to a day-long strike, garnered a promise from the management to release new wages if the workers returned to work. A week later, transport services were cancelled. The workers had no access to reliable public transport or private transport to get to work.

The management told the union, “if you don’t want the cuts, make transport arrangements yourself”. GAFWU gathered evidence that other neighbouring factories were deducting much less than this one and that public transport – be it unreliable – cost only Rs.10 per day. Mustering support on the IVRS platform, the union created a petition – signed by 60 union members – to the labour court and filed a case.

The Kanchipuram district court ruled in their favour and declared deductions for transport at source from minimum wages illegal. GAFWU followed up with a writ petition to ensure payment: two union members were given the authority to collect dues owed by the company in May 2019. The commuters have made transport arrangements with a shared van costing them a little over a quarter of company charges. “Everyone should use the IVRS, so we know what's going on and share widely”, Padmavathi advises.

Initiatives like Shramik Vaani and its Urumai Kural platform leverages the power of IVRS technology to identify solutions to garment worker's problems and use a basic mobile phone to connect workers in galvanizing around these solutions. Since trade unions manage these IVRS lines; once these solutions are identified they can negotiate with factory managements effectively. When one worker raises an issue on the IVRS, the power of the collective leads to solutions. This provides an opportunity to amplify worker participation in improving working conditions to make fashion a force for good.

Breaking the cycle of violence: Stories of courage

20 May 2019

Freedom of association is a right recognised internationally and reiterated in corporate policies of all major garment brands. So, workers have to simply organise and collectively bargain to achieve better conditions? Well, it is not as simple as that sounds. These two women were beaten up in April last year for doing so.

Thayamma, 35, has been working in the garment sector for the past six years. She joined the Karnataka Garment Workers Union (KOOGU) in 2016 and now serves as the joint secretary. The union is her family. Last year, a simple signature landed her in surgery.

On April 3rd, 2018, Thayamma had followed her regular routine to arrive at work. The only irregularity was the brief pause at the factory gate to sign a petition for clean drinking water, better transport and a modest raise. Later in the day, she was pulled aside by a group of managers and co-workers and beaten up severely. She had to be rushed for urgent medical attention and surgery. They wanted her to falsely testify that the Union was collecting money from workers and attempting to close the factory. When she was being strangled, she felt this was the end.

Before I did not have the courage to speak up. I only knew how to cry. Now after regular trainings, union support and attending several meetings, I can stand up for myself. Not only that, I am now strong enough to extend support to co-workers to combat injustice

The low wages and poor working conditions in garment factories are no secret. Women form a majority of that workforce. Despite national laws protecting freedom of association, attempts to do so are often met with resistance. These women are often caught in a cycle of oppression at work and home that unions like KOOGU help break.

Having the courage to speak out

For Deepa Shree, 32, the abuse was continuous, and her fear kept her quiet. Union activists identified her as a victim of domestic violence and supported her in filing a legal complaint against her husband. However, the abuse intensified at work. The attack in April wasn’t the first time that she had been targeted by her supervisors because of her union association. “Before, if a supervisor touched me inappropriately, I would let them due to fear,” she recalls. “Now I know how to stop it then and there. Today if I am sitting here wearing jeans and t-shirt and attending the Union Committee meeting with confidence, I attribute that to KOOGU. I am the opposite of what I used to be before. This has also led to increased respect at work. Now I even stand up for others at the workplace and encourage my colleagues to make written complaints to the human resources department”.

Thayamma and Deepa feel that “being part of the collective is the only way that we achieved the kind of respect, we have today at the workplace and at home.” These two women are committed to stopping fellow workers from suffering the way they had to. Unions have been a transformative force of action to finally give the workers what the needed the most: a collective voice.

One pulling up the other

25 June 2019

"Women are the majority of the fashion industry's workforce, so it's important that they have a voice in order to exercise their rights. I'm proud to be able to fight for improving working conditions and to end gender-based violence in the factory where I work", says factory union leader Salma Khatum, from Bangladesh.

I had a very simple childhood. I was born in the district of Jessore, Bangladesh. My father was a trader, my mother- a housewife. I shared the household chores with her before heading out to play in the street with my friends and baby brother. When I was a child, I dreamt of becoming a doctor to help people. My parents were very concerned about passing on to me values they thought were important in life: they always said it was through studying that I'd become a good human being. They told me not to be greedy, to respect my elders and to love those younger than me. Lastly, they believed I should help others according to my abilities, and that I did what I was able to.

Eight years ago, my parents chose the man I would marry. I was 18 years old. My husband didn't want to take on the responsibilities of my studies, and that attitude created an uneasy situation between us. When I found out he was having an affair with another girl, I decided to file for a divorce. However, the separation led to an uncomfortable atmosphere in the village. People started judging me; I heard horrible things about myself, and I made up my mind to leave. I moved to Dhaka, capital of Bangladesh, and I got a job as a seamstress in a clothes factory. It was there that I took my first steps towards changing in my life.

The first steps to fighting for gender equality

At the start, I was a worker like any other, but then I was invited to take part in workshops on labour rights at the Bangladesh Center for Workers’ Solidarity (BCWS), an organisation supported by C&A Foundation, which fights for gender equality and human rights. With the training I received, I was able to join the Workers' Participation Committee, a representative body for those working at the factory, and it became apparent that the rules imposed could be changed if we acted together.

Standing up against exploitation in the factory

My struggle started when, one day, I was verbally assaulted by a man at the factory. I complained to my manager, who did nothing regarding the incident. At that moment, I started demanding better working conditions and showing other women that they could also defend themselves. That they can take action to prevent situations of harassment from occurring.

There was also a lot of pressure in the factory, and we were being exploited. At the committee meetings, I was increasingly talking about labour rights and the issues necessary for improving our environment. I managed to get a large number of women to join the movement, and I became a union leader. We gained power for systematically fighting against repression, and a transformation was underway. Earlier, when we needed time off for a doctor's appointment, our wages for the day were deducted. Now, we've won the right to have paid sick-leave.

I never imagined I'd be able to bring about a change such as this in my workplace. The textile industry's workforce has few qualifications, and most haven’t had formal training. I'm tremendously proud of serving as inspiration for these women. My dream now is to guarantee a decent wage for female factory workers and I want to see the factory free of gender-based violence. Women are the majority of the fashion industry, so it's important that they have a voice for asserting their rights. I hope the women of the next generation keep on fighting.

“It's very important that they have a voice for asserting their rights. I hope the women of the next generation keep on fighting.”

My work with female workers in the factory and the skills that I have developed has also led to change in my own life, that of my family and the people around me. I'm 26, and I live with dignity, knowing I'm making a difference. As I once dreamt of being a doctor, I'd like to see my son, nine years old Tamim Mahmud, study medicine. I'm a single mother, and I think a lot about his future; I'd like to set an example. I'll pass on all of the values and lessons my parents gave me, and I know he will respect female workers and help them any way he can".

The above text is part of a series of profiles published in the Brazilian edition of Marie Claire, in partnership with C&A Foundation. The original version can be read here.

A collective journey towards autonomy

20 August 2019

Ana Claudia Alves da Silva had a happy childhood with her siblings in the Brazilian capital of Brasilia. She started a family when she was quite young and lost her husband at just 21 years of age. With four children to raise, she decided to find a more peaceful place to live, where her children could grow up safe and happy. She packed their bags and said farewell to the big city, heading off to Novo Zabelê Settlement, a small rural community located in the interior of the State of Piaui, in north-eastern Brazil.

There, Ana Claudia resumed her studies and graduated with a Level 4 diploma in Business Administration. It was then that she became involved with the organic producers’ organisation in the municipality, helping to improve the group's marketing, accounting and putting into practice knowledge that she acquired from her course of studies.

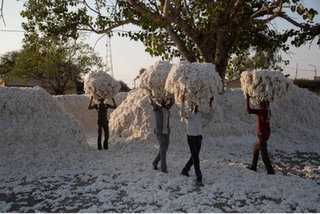

Today, in addition to being a farmer, Ana Claudia is also a secretary who sits on the executive committee of the regional farmers’ association. In Brazil, these associations are known as Participatory Organic Assessment and Compliance Organisations (OPAC, by their Portuguese acronym). Today, the OPAC where she works has the mission of certifying locally produced organic cotton. It serves approximately 30 farming families.

When cotton is certified as organic, it increases in price as a value-added product, benefiting the farmer. In communities where OPACs are present, this certification depends on the collective assessment of the farmers in the association; that is, the community assesses itself, and its members work together to ensure that they are all meeting the requirements for becoming organic producers.

“From the moment a product is certified as organic, it not only gains more credibility, but we also get an added value for it. This certification values our work as farmers as much as it values the product itself", Ana Claudia explained.

Collective organising

"Growing Cotton in Organic Intercropping Systems” is a project that is being implemented by the NGO Diaconia, with support from C&A Foundation. This project is bolstering organic production in six states in Brazil's semiarid region by providing technical consulting and by incentivising collective organizing in organic farming communities through OPACs.

Ana Claudia says that the work done in her community is very important, because Diaconia and the local NGOs that are project partners, do not dictate what is to be done but instead demonstrate the strength and potential of the women workers and their male colleagues, showing them that they canbecome stronger by acting collectively.

“The NGOs that partner with Diaconia in the communities where the project is being implemented play a key role in getting people to appreciate the diversity within each region and in helping people to organise themselves”, Ana Claudia said.

This kind of teamwork has already led to a lot of progress. One area of advancement is a new website for marketing their organic produce, selling the fruits and vegetables grown by the farmers in the region. Even though the site was only recently launched, a lot of purchasing is already happening there. Currently, the site is aimed only at consumers in the city, but there is already a plan under consideration to expand it to other regions in Brazil.

In addition to boosting technical consulting and marketing in the countryside, there is also an incentive to make the sales process increasingly transparent.

“For us, producing cotton with the knowledge of who the end consumer will be is a more secure approach. It's no longer acceptable for farmers to produce a large harvest and then not know who to sell it to. Today, the OPAC helps to sort that out", Ana Claudia explained.

In recounting the history of her organisation, Ana Claudia described the struggles the community had and the obstacles it faced, and she is satisfied with the work that they have been doing.

“Today, we're very proud of our history, because everything we built back then has kept us going the distance and now we're reaping the good fruits of our labour", she noted.

Women leading the way for financial freedom

According to Ana Claudia, there was a sense previously that the women farmers were not fairly compensated compared to the men—but that situation changed once the association came into the region. Today, she sees women providing for themselves and, moreover, joining in the decision-making processes by serving in various roles within the OPAC.

“The OPAC's greatest strength is its women", Ana Claudia said. “We’re the ones who’ve kept this association going in every respect. From organising the meetings to managing the finances, it's us women who are leading it. And we do so with tremendous pride!" she added.

The gains made through their collective efforts not only have raised their incomes but have also improved the way their community is organised. It has given voice to the women farmers and opened up space for them so that today they feel much more independent and empowered.

“Everything we’ve built in recent years just can't be for nought. The woman farmer has come of age. She’s no longer that woman carrying a bucket of water on her head, with a bunch of kids running beside her. She’s no longer that woman. She's a beautiful woman—she's the woman who plants cotton", Ana Claudia said.

About Diaconia

Diaconia is a C&A Foundation partner that helps to empower female organic farmers, as well as male farmers, and that works with regional organisations to promote sustainable cotton production in Brazil.

Earthquake: Community reconstruction and strengthening

Connecting for collective action

One pulling up the other

Breaking the cycle of violence:

Stories of courage

A collective journey towards autonomy

Five reflections from our team members

Gender, Equity and Inclusion: The C&A Foundation Journey

10 September 2019

Consider who you think of when we ask you to picture a corporate leader, investor or factory manager. Now think about who you imagine assisting you at the service counter in a retail outlet, or modeling the clothing, or sewing the garments.

When it comes to gender, we are conditioned to recognize women as shoppers, retail workers, and factory workers. They are much less often the decision-makers. And to a certain extent that stereotype holds true, even though women make up about 80% of all apparel workers. That’s why a few years ago, we embedded a theory of change addressing Gender Justice into all of our work. Because we believe that to fundamentally transform fashion into a force for good, we must address this gender dynamic.

Gender dynamics affect men AND women, and of course gender non-conforming individuals. Our approach isn’t a ‘women’s empowerment’ approach. It’s not just about women; it’s about changing social dynamics. Gender Justice is the term we chose to describe this approach.

In our journey to understand and address gender, we have come to understand the complex, cumulative way in which the effects of multiple forms of discrimination – including racism, able-ism and homophobia- combine, overlap or intersect to reinforce gender inequity. In many of the countries where we work, the women and men who make, sell and buy our clothes may come from communities held back by deeply entrenched systems of discrimination and exclusion.

Our industry cannot thrive if this continues to be the case. So in 2018, we issued a Statement on Equity and Inclusion. We made a series of commitments in that statement. Importantly, one of our key commitments was to transparency- to communicate our progress as well as our setbacks. This is one of many updates we will share with all our stakeholders in the spirit of continued transparency.

In 2018, we commissioned a Benchmarking Report to help us evolve a comprehensive and holistic approach to gender, equity and inclusion both within our own operations, and in our grantmaking.

We are looking at this holistic approach both internally and externally, and both with respect to safeguarding and preventing harm and affirmatively supporting a workplace culture in fashion that embraces our differences and is truly inclusive. We are implementing an ambitious Gender, Equity and Inclusion Action Plan to both our internal operations and policies, our grantmaking. And in 2019, we continued our learning journey through a Gender Justice Learning Partnership.

Through the partnership, different teams within the foundation have been able to better understand gender justice. In Brazil, a seasoned gender and social inclusion expert gave a series of workshops to our staff and made field visits with partners to deepen our ability to apply a social inclusion lens to every activity we support. Learn more about the main insights and lessons learned as a result of the workshops in Brazil. In Mexico, our field office staff worked with a local and expert civil society organization (ILSB) to embed gender and social inclusion in their internal and external work, as well as convene civil society and donors to discuss how the foundation could help to progress the gender agenda in the country. Finally, some of our Mexican partners received support to embed gender justice into their own structures and the initiatives with C&A Foundation.

We still have much more work to do, but with this ambitious internal diagnostic of our workplace culture and grantmaking we will be able to refine our Gender, Equity and Inclusion Action Plan. And we’ll be celebrating some of our partners and our shared successes this year at the upcoming Women Funded conference in San Francisco- join us for the panel on Gender Equity in the Apparel Industry!

Transparency: not just a motto, but definitive action for transforming the world

20 May 2019

The fashion industry has a troubled history when it comes to transparency. Known for having a highly complex, fragmented and difficult-to-trace supply chain, the business model often means a limited overview of what conditions clothes are produced in, opening up gaps that can lead to workforce being exploited. From the famous 1911 fire at New York's Triangle Shirtwaist Company factory, which killed more than 140 workers – mostly women, and which led to the fight for women's rights – up to today's decentralised and highly complex models that make it hard to hold brands accountable, the industry has more than its fair share of negative incidents.

Within the fashion industry, a number of impressive initiatives are beginning to gain importance and signal a change in course. One of the most important of these initiatives is the creation of the Fashion Revolution movement in 2013, which emerged in response to a textile factory collapsing in Savar, Bangladesh, killing more than one thousand workers. The movement encourages reflection on fashion's cost and impact on both society and the environment. Fashion Revolution promotes debates on sustainability at events and workshops around the world to call for a fairer and transparent fashion industry.

Transparency: A tool for workers to consumers

For brands to become increasingly sustainable, Fashion Revolution believes in transparency as a fundamental leverage. In 2016, Fashion Revolution created the Fashion Transparency Index, setting out technical parameters for assessing the quality of information major brands provide the public on their practices. The index is updated annually, making it possible to draw comparisons and demonstrate improvements in the transparency levels of every brand assessed. The 2018 global report identified improvements of approximately 10% for 16 companies, which indicates the effectiveness of the index to inspire brands to become more transparent and accountable of their practices.

In recent years, the fundamental demands from the public, the call for more transparency, and the improved availability of information has led to a significant change in the paradigm of how private institutions act. Whereas previously, concern regarding the supply chain was confined to engaged groups with little impact, this is now changing among consumers, who often demand greater transparency from companies on their social, environmental and labour responsibilities. And many consumers are starting to use this criterion when deciding which products will and won’t make it into their shopping bags.

Faced with this reality, corporations are starting to seek out initiatives to make their activities more transparent. In Brazil, it is worth mentioning the work of Abvtex – the Brazilian Textile Retail Association. Through a Supplier Certification Programme, they aim to prevent practices that exploit labour in its associates’ production chains. Abvtex recently started publishing a list of every certified supplier, updated daily and available on the association's website.

Driving change on many levels

On a global level, the Open Apparel Registry, launched a platform in 2019, which makes it possible to geolocate factories and their respective partners around the world, on an interactive map. The platform is based on information already made publicly available by brands, but as an open-code initiative,it also allows any user to add further information. The call for a minimum standard of transparency is also the main objective of the Transparency Pledge, which is led by Human Rights Watch. Together with brands, the Transparency Pledge conducts campaigns to publish information, on every factory within the brands supply chain, in a standardised and therefore comparable manner. The process is only publicly recognised once various criteria has been met, such as guaranteeing ease of access and the clarity of information provided on products and recording the percentage of all suppliers participating in the final production amount. The information has to be updated constantly, to encourage changes to be monitored continually and positively.

Nevertheless, even with the countless positive examples of increased transparency, there are still challenges to overcome. The main obstacles to alny initiative are language barriers and accessibility in making information available.Data is frequently published without previous planning to establish a target audience, or forecasts of the effects it will cause both decision-makers and those to be held accountable. Further precautions are also required, such as defining consistent measurement criteria, the frequency of disclosure and, above all, the availability of information that is effective in creating real transformations.

The concept of transparency and the actions to promote it are based on assumptions much more complex than sporadic communication strategies. To get satisfying results, measures encouraging behavioural and structural transformations must in fact be adopted, placing relevant information in the hands of actors capable of pressurising decision-makers to make that change.

The path is an arduous one in any large-scale production sector, and not just in the fashion industry. It involves a continuous process, in which the most significant cornerstone is promoting a cultural change so marked that it makes corporations view their activities in a more comprehensive manner. This goes through various revisions – including when devising business plans – which should treat transparency not as an afterthought, but rather a common thread in every strategy. Decision-makers being accountable is key for the production sector to be truly aligned with its consumers' interests, guaranteeing decent working conditions for millions of workers- thus setting a strong transformation/ strong transformative wave in the world economy into motion.

* The opening photo of the article was taken at the launch of Fashion Index Brazil 2018.

Improving Farmer Livelihood, One Drip at a Time

14 November 2018

At a time when it seems like the world is falling apart, success stories that illustrate how small efforts can make a big difference feel like balsam for the soul. I am lucky enough to be a part of a small team working to make an impact in the lives of cotton farmers in my home country of India.

Farmers in India, especially smallholder farmers, are facing unprecedented challenges. Issues like water scarcity and the growing risks associated with climate change, poor soil fertility and loss of biodiversity, and farmer poverty are threatening the very fabric of rural Indian life.

Recognising this threat, and in particular that of water scarcity, the Government of Gujarat created a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) called “Gujarat Green Revolution Corporation” (GGRC) to provide subsidies to farmers to install drip irrigation. This modern agricultural technique that irrigates crops with tiny droplets of water, helps farmers save time, money, and water. The GGRC subsidy, which can vary from time to time, currently covers about 70% of the cost of installation, with the remaining 30% left to be borne by farmers themselves.

Sounds straightforward. The problem is that smallholder farmers usually do not have the resources to pay the remaining amount for drip and they cannot obtain formal credits because they often lack documentation and collateral. Without formal credit institutions to service them, farmers are left with no choice but to borrow money at exorbitantly high rates from informal moneylenders. So, despite the GGRC subsidy, drip irrigation remains a luxury that only medium and large-scale farmers can afford.

To bridge this gap, C&A Foundation in partnership with Aga Khan Foundation and Aga Khan Rural Support Programme India, established a community funding mechanism to provide interest free loans to smallholder cotton farmers in the Saurashtra region of Gujarat. With their loans, farmers have been able to pay the remaining amount, avail the GGRC subsidy, and install drip irrigation on their cotton farms. As farmers repay their loan, within a period of two years, the amount goes back into a “community managed fund”, which is managed by the community farmers groups and is used to give further loans to other farmers.

At C&A Foundation, we have been working with this Drip Pool Programme for several years, during which time I have personally been able to witness the value of this scheme not only for the farmers but also for the environment. Now, thanks to the data gathered in our new report “Bridging the credit gap: Water sustainability through innovative financing , we are finally able to prove it.

First and foremost, the report shows that in 2017-18, farmers in the programme have been able to achieve a net income 31% higher from their cotton cultivation compared with farmers that are not using drip irrigation. That is about Rs 22,575 (EUR 301) per acre, compared to Rs 17,325 (EUR 231) per acre reported by farmers without drip irrigation. And thanks to this increase in income, the quality of life has increased for their entire households. A farmer called Vallabh explained this as such:

“When there was no drip we had to pump water from the well. We had to get up at night to create a canal for the water and then stand while that canal filled up. It needed many of us and labour was expensive. Now, the men we required for irrigation can be used in other places and we can grow vegetables and peanuts.

When we didn't use drip, we used to spend around Rs 70,000-80,000 (EUR 930-1,060) a year on irrigation, making just Rs 10,000-15,000 (EUR 130-200) profit a month. After drip, we have been able to increase our profit to Rs 25,000-30,000 (EUR 330-400) a month.

That money is now invested in my children's education. Before we couldn’t do that. And our houses have changed. Earlier we used to stay in huts, now we have a new concrete house. Because of the costs that have reduced due to drip, the lifestyle that we could not afford earlier, even food and shelter, we have been able to do that.”

But the programme has yielded far more benefits that “just” an increase in income, with farmers seeing environmental impacts as well. Programme farmers have reported using just 1,191 litres of water per kilogram of cotton, compared to the 5,923 litres consumed by non-drip farmers; or in other terms, an acre of cotton cultivation under the programme uses around 2.5 million litres less water compared to peers. And drip irrigation also helps to conserve soil fertility by avoiding top soil erosion and making the fertilisation process more efficient.

One of my favourite impacts has been the effect on the farming communities. At the community level, Farmer Interest Groups (FIGs) have been formed to keep track of the loans taken by farmers. These groups have become a vital, vibrant part of community life and they are used to discuss issues related to agriculture. The FIGs then are federated to form Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs), that are not only responsible for overall management of the fund but also help the farmers to purchase their inputs and access markets as a collective. This kind of ownership on the community level will help this programme live on long after C&A Foundation and its partners have left.

To keep up with mounting agricultural challenges facing India, we need to start thinking out of the box. C&A Foundation’s Drip Pool Programme shows that multi-stakeholder partnerships with strong community ownership can help create environmentally and financially sustainable agricultural systems that promote not only the health of ecosystems, but also of the people who depend on them.

Straight talking on circular fashion

12 August 2019

What exactly is a circular fashion business model?

We need to put the brakes on the runaway environmental and social impacts of fashion. Both society and the environment are paying too high a price for our insatiable desire for clothes.

As the sustainability of fashion supply chains come under greater scrutiny, some in the industry see the circular economy as part of the solution. Indeed, the idea of fashion made with safe, non-virgin and renewable materials that are endlessly used and reused is promising. But for this to be achieved, we need to think beyond recycling or getting another use out of a garment. Circular fashion can only happen when the industry’s current business models are radically transformed into circular models.

But what exactly is a circular fashion business model?

For all the buzz around circularity, the sector still does not have a shared definition of a “circular business model”. There is, however, an emerging narrative that new business models will shift from clothing as something to own to something that performs a service. In State of Fashion 2019, the report identifies “end of ownership” as an ‘emerging consumer shift’, based on a study of 2,000 American women, noting consumers are demonstrating an “appetite to shift away from traditional ownership to newer ways in which to access product.”

The thinking here is that customers do not need to ‘own’ the materials that make up their clothes, and they do not have the capacity to turn old or unwanted clothing into future resources.

With ‘service’ or ‘performance-based’ business models, the ownership of the materials shifts from the customer to the company. This gives businesses a financial incentive to invest in both designing and manufacturing their products, so that they can be recovered and re-used as raw materials. The higher the quality of the materials recovered, the more profitable the business model.

But this radical change in business models won’t happen overnight. It needs a considerable amount of experimentation, starting with scaling certain elements of circular business models. The good news is that there is evidence this experimentation is already underway.

The London Waste and Recycling Board together with circular economy business consultants, QSA Partners, have identified over 50 companies implementing elements of circular business models such as digital services, subscription models, hire services, product resale, sharing services and increasing product quality. And the global innovation platform, Fashion for Good, has scouted 50 start-ups that offer platforms or services for circular business models.

At the same time, the social enterprise Circle Economy, in partnership with the Finnish Innovation Fund SITRA, published ten deep dive case studies of businesses that create value from waste, sell functionality over ownership and encourage effective resource use.

In the meantime

These early efforts will help to establish a much-needed common definition and framework of circular business models in fashion. But as that takes shape, we must continue to challenge and stretch the capacities of current business.

Many forward-thinking organisations are doing just that. And in addition to the above initiatives, the World Resources Institute in partnership with WRAP is also helping apparel and footwear companies innovate towards circular business models. To support the scalability of their work, they have a formed a working group called ‘Bridging the Gap’.

In addition, Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s Make Fashion Circular initiative calls for sector-wide collaboration with a view to building a compelling, evidence-base narrative to supports these efforts.

All of these moves are designed to deliver organisational change, build a powerful case for circular business models, and contribute to the transition to ‘good fashion’. And in this process, a common definition should evolve.

As we work on building definitions and frameworks for a circular economy in fashion, we must never lose sight of the goal – to create an industry that uses safe, non-virgin and renewable materials endlessly. The more we experiment, test and prove, the more robust these will be become and the closer we will get to reaching that goal.

This blog was originally featured on the Ecotextile website, click to see the original.

Constitutional Labour Reform in Mexico: and now what?

30 October 2019

Enforce. This is the verb that I have read or heard the least in relation to the 2017 Constitutional Labour Reform in Mexico. I think it is altogether fitting to welcome these changes to the nation’s constitution, as well as those that were promulgated on 1 May 2019 relative to the Federal Labour Law (LFT). However, as with all reforms in any country, the greatest challenge could lie in its enforcement.

This new Labour Reform law will be able to remedy the delays that workers face in accessing the justice system, which is something that is being applauded by the citizenry, myself included! Even so, this is no time for us to be sitting idly by, since the labour justice problems in Mexico could have been solved years ago if only the law had been strictly adhered to: “According to the law that was in effect before this reform, a claim for wrongful termination should not take more than 105 days to settle, but that figure surely elicits laughter from labour attorneys, who are used to trials that go on for years" (Kaplan, 2019).

Another challenge is how to bring about government transformation, changing how the government operates and understanding its role under the new system. Up until now, we have seen some positive signs from the Legislature and the Executive towards making the necessary changes to the LFT, as well as towards establishing the Coordinating Council for the Implementation of Reforms to the Labour Justice System (CCIRSJL, as it is known by its Spanish acronym) (Ministry of the Interior, 2019). However, there are still many open questions about how this reform will be implemented. Just to mention a few:

What is the budget for this? If we imagine that "budget is love", it would seem that the implementation of this reform is lacking in public servants and legislators who at least want to show their affection for it. This is due to the lack of evidence that decision-makers have regarded the necessary budgetary requirements for carrying out this reform (creating an administrative body, establishing labour tribunals, and getting rid of the Board of Arbitration and Conciliation (Ponce, 2019). It is estimated that the administration of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador will need to invest 2.2 billion pesos (€103 million or £91 million) during his six-year term of office (Hernandez, 2019), and this amidst the national government’s current austerity programme, which is already affecting public services delivery. So, I wonder: Have they run all the numbers? Will the government really be able to invest the amount needed?

What about the Judiciary? Clearly, the number of jurisdictional bodies must be increased in order to handle the 100,000-plus labour trials each year (Soto, 2019), and that will set in motion a specialised human-resources recruitment process—but again, do we have the budget for that? Moreover, it is unclear how to train the public officials (including judges) who will be responsible for implementing and enforcing the labour reforms. This is a matter of extreme importance if the labour tribunals are to be able to do their work. The training must be completed within three years at the local level and within four years at the federal level. Hence, we have to ask ourselves: Is that enough time? Who will be providing these trainings, and who will be monitoring their quality and their completion rates?

And the labour unions? In the words of a small, independent labour federation, "We may have a lovely law, but it's not going to be easy. We’ve had a lot of years of control and manipulation" (Malkin, 2019). In Mexico, the problem with yellow unions (company unions or unions led by pro-management union leaders) is explained by the Mexican saying that "You can't teach an old dog new tricks.” That largely applies to this case. Strict implementation of the Labour Reform will be crucial for giving the following ultimatum to those unions that are not representing their members: in essence, change or die.

What about the private sector? It is clear that this is not the reform that the private sector would have wanted (Ponce, 2019), since it democratises labour relations between employer and employee, thereby making it increasingly more difficult to violate workers’ rights. Nevertheless, the private sector needs to keep discussing with the authorities to ensure that the LFT includes the necessary elements to avoid having to compete with other countries solely on the basis of low wages. Likewise, it seems important to me that the private sector have a seat on the CCIRSJL, due to the fact that it will also be a user of labour tribunals and we need to ensure that they are working for all parties involved.

How are garment industry workers affected? Last but not least, workers in the the garment industry must join forces and request that the regulatory framework be implemented and their rights guaranteed. This is a huge challenge for factory workers who face poverty, job insecurity, and workplace violence. The Labour Reform implementation must, to a large extent, settle an historic debt that the state has with apparel industry workers: the right to collectively organise themselves without retaliation and/or dismissal (basically guaranteeing freedom of association in a country where close to 80% of all collective bargaining agreements (i.e., nearly 400,000 of 500,000 in total) are in fact protection contracts(24 Horas, 2019).

In conclusion, we must be persistent. From where we sit in civil society, we must support, monitor, and bolster the implementation process. Our role is to bring visibility to these problems, recommend alternative solutions to the government and bring the key players together around the dialogue table. It is through research and political activism that we are able to recommend improvements (or corrections) to those areas of the regulatory framework that fail to promote horizontal labour relations and where workers end up losing out. Likewise, we must verify that the law is being obeyed and that it is fostering respect for workers’ rights. It is precisely in this space that private and corporate philanthropy find fertile ground to support activists who are devoting their lives and energies to this struggle.

Gender, equity and inclusion: The C&A Foundation journey

Bama Athreya

10 September 2019

Transparency: Not just a motto, but definitive action for transforming the world

Mariana Xavier

16 May 2019

Improving farmer livelihood, one drip at a time

Litul Baruah

14 November 2018

Straight talking on circular fashion

Megan McGill

25 February 2019

Constitutional labour reform in Mexico: And now what?

Stephen Birtwistle

30 October 2019

Our previous Annual Reports

Read our previous Annual Reports to learn more about the accomplishments of C&A Foundation and its partners.

Annual Report

2018

Annual Report

2017

Annual Report

2016

Annual Report

2015

Annual Report

2014

Redefining value for the good of all.

Laudes Foundation was launched in January 2020 to address the dual crises of inequality and climate change by supporting brave, innovative efforts that inspire and challenge industry to harness its power for good.

Laudes Foundation is building on the lessons learned from C&A Foundation, and is committed to advance its work to transform the fashion industry.

Momentum is clearly building. But not fast enough. To make fashion a force for good, Laudes Foundation will channel the productive power of capitalism on a global scale so that it truly benefits people and respects nature.

Follow Laudes Foundation